The other day a friend and I took a short roadtrip. When I came to pick her up, her 5-year-old grandson was disappointed to be losing her company. “My grandma has too many friends,” he said. She replied, “You can never have too many friends.” He retorted “yes you can,” and would have done so indefinitely, I am sure, had she not told him to go wake up his mother.

So who’s right?

Middle English frend, from Old English frēond; akin to Old High German friunt friend, Old English frēon to love, frēo free. First Known Use: before 12th century

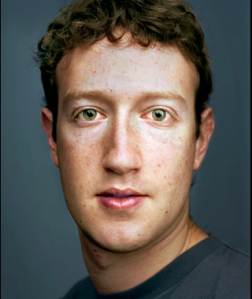

To start with the film: leave it to Sorkin and David Fincher to create the perfect movie to tell their version of Facebook’s founding; the film’s music, script and design hit the perfect pitch of slick to make you want to be invited to the party – the driving force behind their Zuckerberg.

The man himself, who rented out theaters to have Facebook employees see the movie, brushes this off. To Grossman, he explained thus: “The biggest thing they missed is the concept that you would have to want to do something – date someone or get into some final club – in order to be motivated to do something like this. It just like completely misses the actual motivation for what we’re doing, which is, we think it’s an awesome thing to do.”

The man himself, who rented out theaters to have Facebook employees see the movie, brushes this off. To Grossman, he explained thus: “The biggest thing they missed is the concept that you would have to want to do something – date someone or get into some final club – in order to be motivated to do something like this. It just like completely misses the actual motivation for what we’re doing, which is, we think it’s an awesome thing to do.”

Why awesome? “The thing that I really care about is making the world more open and connected…Open means having access to more information, right? More transparency, being able to share things and have a voice in the world. And connected is helping people to stay in touch and maintain empathy for each other, and bandwidth.” Grossman goes on to suggest that it’s Zuckerberg’s real life happy little social circles that inspire his wanting to make the world into one big family.

And he does take a brief time out to describe and dismiss a potential third Zuckerberg – the guy who wants to steal all of our information and sell it to the highest bidder. I’ll leave you to read the article to find out why that’s bogus. The TIME piece really is an interesting and well-written analysis of Fbook and the internet of the 21st century. Take this, for instance:

[Facebook] suspends the natural process by which old friends fall away over time, allowing them to build up endlessly, producing the social equivalent of liver failure. On Facebook, there is one kind of relationship: friendship, and you have it with everybody. You’re friends with your spouse, and you’re friends with your plumber.

Too true, right? I just went to “Edit Friends” on my profile (which itself is a real verbal treat), and checked my 51 “A” first name buddies. I have spoken, in person, in the last twelve months, to 18 of them, and many are students.

And don’t act like you’re better than me.

So it isn’t a case of “will the real Mark Zuckerberg please stand up?” The point at issue here is not why was this made, but why are we using it? I think Jesse Eisenberg’s performance in the film highlights this – the movie ends (not a real spoiler, but…) with him refreshing his laptop, waiting to see if someone will accept his friend request. His stare is blank – a characteristic of the real man, but for a different reason: Zuck’s lights go out when he’s not getting useful information out of you – Eisenberg goes eyes-dead at various points in the film, I think to demonstrate that he really doesn’t see a point to any of it. Sorkin’s writing is better than Grossman makes out. Eisenberg gets invited to the party. Big deal. He gets the money. Not the point. But what is it? He gives us no answer because he doesn’t have one. He likes playing with this big shiny toy – it’s “awesome,” as Z-berg said.

Full disclosure (and how tired are you of that trending phrase?): I am a facebookhead. Recently I’ve been amazed by how easy it is to get and spread information about nonprofits, so I can see where POTYear Zuck is coming from. But I also remember first impressions of social networks: listening through the wall as a college roommate looked up a person in his class, seeing if he had given any hints as to relationship status. I remember tagging a friend in a photo, not thinking he would be embarrassed by it, and having him retaliate by tagging multiple ones of me dancing to Whitney Houston. I mean, there was a time that was every Friday, so now you know. You’re welcome.

And all that crap. And I certainly have plenty of memories of cycling through people’s photos and walls and all the rest of it – so I understand Eisenberg’s endgame too, clicking refresh refresh waiting for something real to happen. Clicking and coding and uploading simply because it’s there, and not having any real conception of what it means for the future.

Maybe we’re still leaving that stuff, the philosophical stuff, to our parents (and then they join Facebook, and…the horror). Part of the allure here for people like me has to be the idea that we’re present at the revolution. Zuckerberg, I was surprised to find out, is just a year older than I am. And so when grayhairs in Newsweek come out with articles like “The Secret Cost of Using Facebook,” we dismiss them as we dismissed the people who kept calling it “the” or “a facebook” for two minutes too late. Yeah, I get that I’m being sold ads based on my drunken photos and I get that none of this is ever going to truly disappear, alright. And while we’re at it, I get that what Julian Assange and Wikileaks did probably damaged international relations. I get that this all might be cruising to some very very bad conclusion. But it’s going to be very very bad for everyone.

There’s a part in the film where Sean Parker, the Napster dude, is excitedly talking about how we all take more pictures so that we can all upload more pictures so that we can all scroll through more pictures, and he says that people used to live on farms and in cities, but now they will live in the internet.

We all know where that gets us. And it is not good for Jeff Bridges’ Zen thing, man.

In Part 2, we’ll see what happens when we plug into the grid.

January 1, 2011 at 10:58 pm

http://news.yahoo.com/s/nm/20101231/lf_nm_life/us_banished_words

Fodder for you…

January 25, 2011 at 10:56 am

You mean you don’t STILL spend most weekends dancing to Whitney Houston?

I really love reading your writing because it’s sort of like I’m getting Daniel Glenn “curating” current events/issues for me. And I say the following sincerely and without any sarcasm: your opinions and reflections are well-considered and trustworthy, and I find that your posts help me choose both what issues to think about and what perspective to take on them. Keep up the excellent work, please.